Chinese Ink

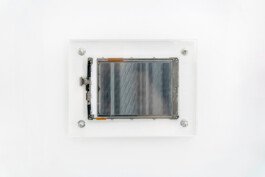

2018.

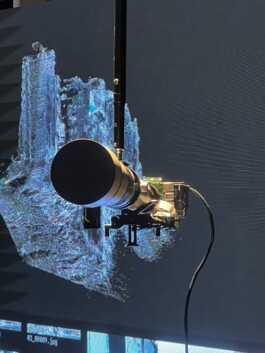

Electronic ink screens, neural network, custom produced dataset, custom designed liquid-cooled server; custom e-ink video playback software driver.

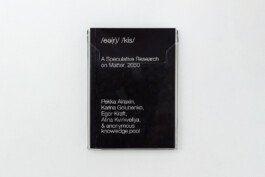

Hashterms

A speculative concept describing an emergent aesthetic system that arises from autonomous processes rather than from direct human intention. The term combines auto- (self, autonomous) with aesthetics, suggesting forms of perception, judgment, or sensibility generated by machines, algorithms, or self-organizing systems.

Relates to technocultural pluralisms; the term refers to concepts developed by philosopher Yuk Hui.

It relates to technological literacy in the same way that one relates to spiritual or mystical knowledge.

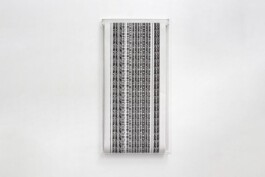

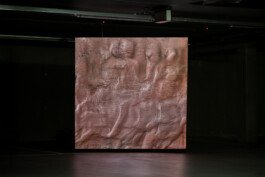

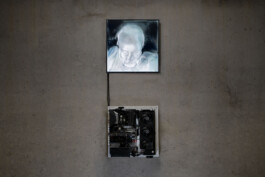

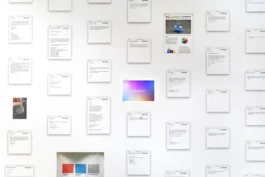

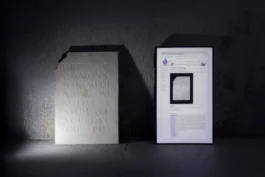

In the installation titled Chinese ink, e-ink screens display a moving image generated by an AI system in real time. The system, trained on inkblot images, renders visually similar content at hundreds of samples per minute. It uses a GPU server with liquid-cooled hardware containing an ink mix. Unlike conventional screens that emit light, e-ink displays mimic the look of ink on paper by arranging nano-sized pigment particles with electromagnetic waves across the display’s surface. The installation draws on the material qualities, aesthetic features, and historic resonance of the ink wash painting technique. It asks how this traditional technique will survive industrial revolutions and their impact on visual media. Does it hold up to being called inkblot when each image is unique due to its computationally random and algorithmically authentic nature?

Will the richness of shades of grey and subtle details of ink soaked into thick rice paper be reproducible through computational simulation? The series is a visual meditation on tracing links between traditions, industrial processes, tools, emerging aesthetics, and formerly dominant visual languages of old civilisations as they undergo intense industrial transformations.

In the installation titled Chinese Ink, e-ink screens are set to display a moving image generated by an AI system in real-time. The system is trained on images of inkblots and set to render visually similar content at the rate of hundreds of samples per minute. The training data was comprised of a thousand scans of inkblots on cold-pressed paper sheets. The algorithm is computed via the GPU server in an open-frame wall-mounted configuration; its hardware is liquid-cooled with the solution containing an actual ink mix that circulates throughout the machine.

The installation calls on the traditional Chinese ink wash painting technique. In focus here: not the style or iconography, but rather the material qualities of the ink, its aesthetic features and historic resonance.

How will this traditional technique continue to exist amid industrial revolutions and their effect on visual media? Will the richness of shades of grey and subtle details of ink drops soaked into thick rice paper be reproducible through computational simulation of this ancient technique? Does it hold up to be called inkblot when each image is unique only in its computationally random and algorithmically authentic guise?

Unlike conventional screens emitting light, e-ink displays are engineered to mimic the look of ink on paper by arranging nano-sized pigment particles with electromagnetic waves across the display’s surface. Are millions of tiny, electrically charged pigment particles suspended in a clear fluid within microcapsules of e-ink displays capable of rendering images as rich in detail as those made with water-based inks? The series Chinese Ink is a visual meditation on tracing links between traditions, industrial processes, tools, emerging aesthetics and formerly dominant visual languages of old civilisations as they undergo intense phases of industrial transformations.

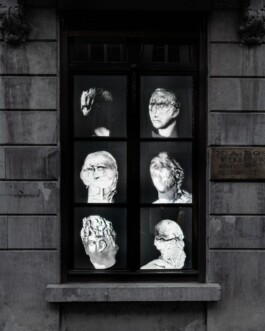

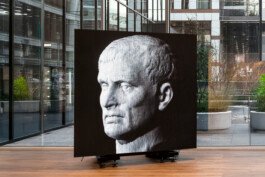

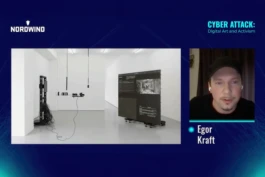

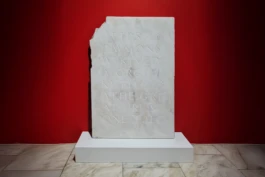

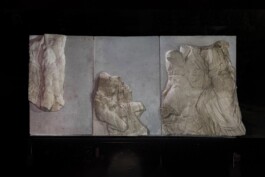

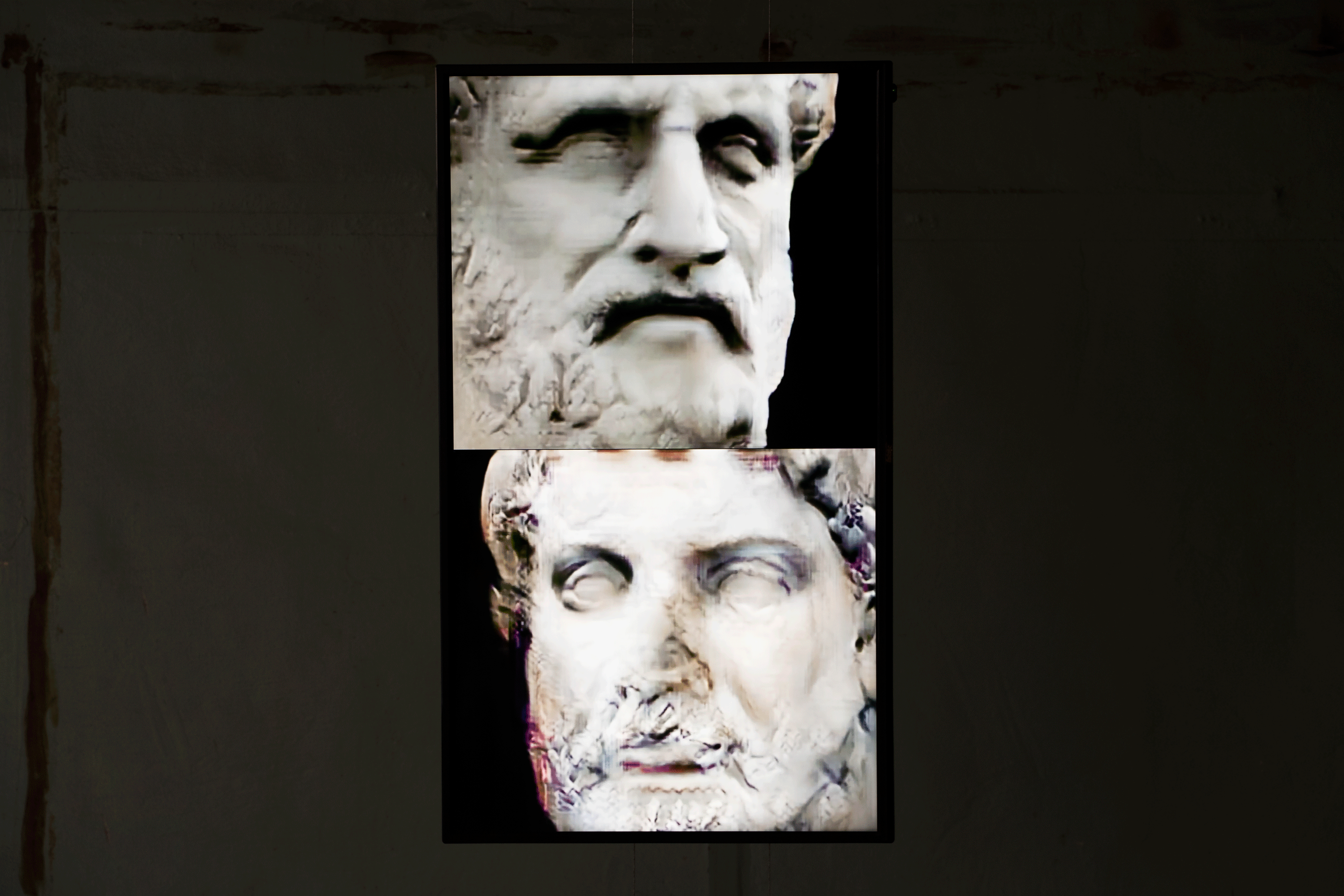

The display of 'Chinese ink' at the 'Artificial Intelligence & The Intercultural Dialogue' event in Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia in 2019 highlights the intersection of traditional art practices with modern technology and the significance of intercultural exchange in the digital age. It showcases how AI can be used to celebrate and preserve cultural heritage, creating a platform for dialogue and understanding between different cultures.

Algorithmic aesthetics and ontology.

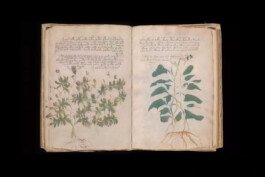

Notes on Chinese ink

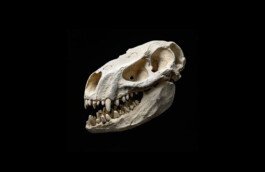

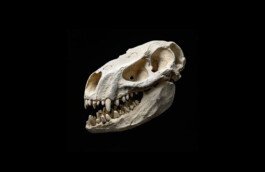

Recent studies in the field of artificial intelligence (in particular generative adversarial networks) have demonstrated outstanding results in the synthesis of hyperrealistic imagery [e.g. neural network Style Gan 2, https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.04958]. Along with the rendering of photorealistic images, data scientists and machine vision specialists have demonstrated extraordinary capabilities of the aforementioned class of artificial neural networks in simulating artistic techniques and style transfer. The degree of quality and accuracy of those algorithmic outputs strikes the imagination. These developments and the emerging prospect of their further applications and calibrations do pose new challenges in the fields of media, journalism and, of course, artistic production, raising a set of new aesthetic issues. The work Chinese ink is meant to facilitate an inquiry into traditional Chinese ink calligraphy technique; my interest is not related to the imagery, visual style or iconography in Chinese painting, but rather to the physical properties, material specificity and historical connotations of industrialisation of technic itself as seen through the lens of the present context. The way in which the ink behaves - as a material produced from soot and glue of animal origin or sometimes graphite-based mineral types, in contact with a special coarse-grained and pre-moistened paper, still remains superior in certain qualities as opposed to European inks. Radiating black lacquer sheen Chinese ink sticks are rubbed and diluted with water to a thick or thin liquid consistency, which allows for achieving a wide range of shades of black and grey, such depth and tone richness had hardly been achieved with European inks. In China ink is considered the cult of tradition and state-of-the-art technology. The work Chinese Ink visually examines applications of the generative-adversarial network in the synthetic simulation of the original technique.

The neural network is being trained on thousands of inkblot images, a dataset especially developed for the project; An involved machine is capable of rendering thousands of images per minute, similar to those it analysed in the dataset, yet each being unique in its algorithmic authenticity. The resulting images are generated in real-time and sequentially displayed via the means of electronic ink displays. The latter plays a crucial role in conveying politics between the visual and conceptual contents of the work. Electronic paper (also e-paper, electronic ink or e-ink) are display devices that mimic the appearance of ordinary ink on paper. Unlike conventional backlit flat panel displays that emit light, electronic paper displays reflect light like paper, involving particles. These hard-pigmented grains are distributed across microstructural material. There is no surprise that such displays are fabricated in modern China, – the country which also occupies one of the leading positions in application, development and research in the fields of machine learning and AI. The economic, political and industrial conditions of neoliberal globalisation under which the above-described technologies are developed in modern China regulate another pace and purpose as opposed to those, at which production and application of traditional ink technology were maintained for centuries. How do such conditions reconvey visual aesthetic qualities? - an issue raised through this work; it suggests to traceback of a chain of links between tradition, technology, time, economies and techno-political processes leading to automation and new emerging aesthetics and tools that enable them on a material level. The main focus of the research around the work is preoccupied with the processes of formation of algorithmic aesthetics and their links to anticipated traditional visual languages.

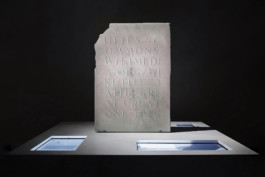

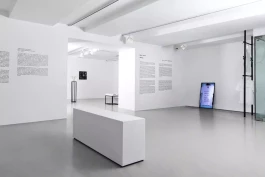

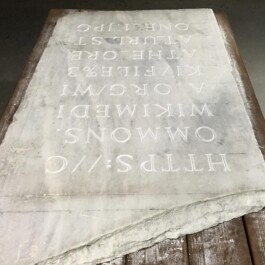

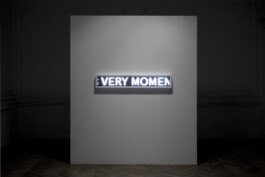

'Chinese ink' at the 'Artificial Intelligence & The Intercultural Dialogue' event in Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia in 2019.

'Chinese ink' at the 'Artificial Intelligence & The Intercultural Dialogue' event in Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia in 2019.

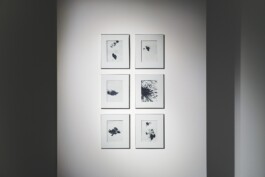

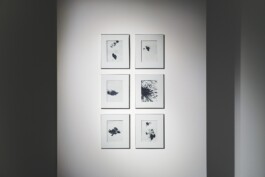

Works from the Series

Chinese Ink

2018.

Electronic ink screens, neural network, custom produced dataset, custom designed liquid-cooled server; custom e-ink video playback software driver.

Hashterms

A speculative concept describing an emergent aesthetic system that arises from autonomous processes rather than from direct human intention. The term combines auto- (self, autonomous) with aesthetics, suggesting forms of perception, judgment, or sensibility generated by machines, algorithms, or self-organizing systems.

Relates to technocultural pluralisms; the term refers to concepts developed by philosopher Yuk Hui.

It relates to technological literacy in the same way that one relates to spiritual or mystical knowledge.

In the installation titled Chinese ink, e-ink screens display a moving image generated by an AI system in real time. The system, trained on inkblot images, renders visually similar content at hundreds of samples per minute. It uses a GPU server with liquid-cooled hardware containing an ink mix. Unlike conventional screens that emit light, e-ink displays mimic the look of ink on paper by arranging nano-sized pigment particles with electromagnetic waves across the display’s surface. The installation draws on the material qualities, aesthetic features, and historic resonance of the ink wash painting technique. It asks how this traditional technique will survive industrial revolutions and their impact on visual media. Does it hold up to being called inkblot when each image is unique due to its computationally random and algorithmically authentic nature?

Will the richness of shades of grey and subtle details of ink soaked into thick rice paper be reproducible through computational simulation? The series is a visual meditation on tracing links between traditions, industrial processes, tools, emerging aesthetics, and formerly dominant visual languages of old civilisations as they undergo intense industrial transformations.

In the installation titled Chinese Ink, e-ink screens are set to display a moving image generated by an AI system in real-time. The system is trained on images of inkblots and set to render visually similar content at the rate of hundreds of samples per minute. The training data was comprised of a thousand scans of inkblots on cold-pressed paper sheets. The algorithm is computed via the GPU server in an open-frame wall-mounted configuration; its hardware is liquid-cooled with the solution containing an actual ink mix that circulates throughout the machine.

The installation calls on the traditional Chinese ink wash painting technique. In focus here: not the style or iconography, but rather the material qualities of the ink, its aesthetic features and historic resonance.

How will this traditional technique continue to exist amid industrial revolutions and their effect on visual media? Will the richness of shades of grey and subtle details of ink drops soaked into thick rice paper be reproducible through computational simulation of this ancient technique? Does it hold up to be called inkblot when each image is unique only in its computationally random and algorithmically authentic guise?

Unlike conventional screens emitting light, e-ink displays are engineered to mimic the look of ink on paper by arranging nano-sized pigment particles with electromagnetic waves across the display’s surface. Are millions of tiny, electrically charged pigment particles suspended in a clear fluid within microcapsules of e-ink displays capable of rendering images as rich in detail as those made with water-based inks? The series Chinese Ink is a visual meditation on tracing links between traditions, industrial processes, tools, emerging aesthetics and formerly dominant visual languages of old civilisations as they undergo intense phases of industrial transformations.

The display of 'Chinese ink' at the 'Artificial Intelligence & The Intercultural Dialogue' event in Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia in 2019 highlights the intersection of traditional art practices with modern technology and the significance of intercultural exchange in the digital age. It showcases how AI can be used to celebrate and preserve cultural heritage, creating a platform for dialogue and understanding between different cultures.

Algorithmic aesthetics and ontology.

Notes on Chinese ink

Recent studies in the field of artificial intelligence (in particular generative adversarial networks) have demonstrated outstanding results in the synthesis of hyperrealistic imagery [e.g. neural network Style Gan 2, https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.04958]. Along with the rendering of photorealistic images, data scientists and machine vision specialists have demonstrated extraordinary capabilities of the aforementioned class of artificial neural networks in simulating artistic techniques and style transfer. The degree of quality and accuracy of those algorithmic outputs strikes the imagination. These developments and the emerging prospect of their further applications and calibrations do pose new challenges in the fields of media, journalism and, of course, artistic production, raising a set of new aesthetic issues. The work Chinese ink is meant to facilitate an inquiry into traditional Chinese ink calligraphy technique; my interest is not related to the imagery, visual style or iconography in Chinese painting, but rather to the physical properties, material specificity and historical connotations of industrialisation of technic itself as seen through the lens of the present context. The way in which the ink behaves - as a material produced from soot and glue of animal origin or sometimes graphite-based mineral types, in contact with a special coarse-grained and pre-moistened paper, still remains superior in certain qualities as opposed to European inks. Radiating black lacquer sheen Chinese ink sticks are rubbed and diluted with water to a thick or thin liquid consistency, which allows for achieving a wide range of shades of black and grey, such depth and tone richness had hardly been achieved with European inks. In China ink is considered the cult of tradition and state-of-the-art technology. The work Chinese Ink visually examines applications of the generative-adversarial network in the synthetic simulation of the original technique.

'Chinese ink' at the 'Artificial Intelligence & The Intercultural Dialogue' event in Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia in 2019.

The neural network is being trained on thousands of inkblot images, a dataset especially developed for the project; An involved machine is capable of rendering thousands of images per minute, similar to those it analysed in the dataset, yet each being unique in its algorithmic authenticity. The resulting images are generated in real-time and sequentially displayed via the means of electronic ink displays. The latter plays a crucial role in conveying politics between the visual and conceptual contents of the work. Electronic paper (also e-paper, electronic ink or e-ink) are display devices that mimic the appearance of ordinary ink on paper. Unlike conventional backlit flat panel displays that emit light, electronic paper displays reflect light like paper, involving particles. These hard-pigmented grains are distributed across microstructural material. There is no surprise that such displays are fabricated in modern China, – the country which also occupies one of the leading positions in application, development and research in the fields of machine learning and AI. The economic, political and industrial conditions of neoliberal globalisation under which the above-described technologies are developed in modern China regulate another pace and purpose as opposed to those, at which production and application of traditional ink technology were maintained for centuries. How do such conditions reconvey visual aesthetic qualities? - an issue raised through this work; it suggests to traceback of a chain of links between tradition, technology, time, economies and techno-political processes leading to automation and new emerging aesthetics and tools that enable them on a material level. The main focus of the research around the work is preoccupied with the processes of formation of algorithmic aesthetics and their links to anticipated traditional visual languages.

'Chinese ink' at the 'Artificial Intelligence & The Intercultural Dialogue' event in Hermitage, St. Petersburg, Russia in 2019.

Works from the Series

Studio Addresses

Ikejiri, Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan

Neubau, Vienna, Austria

Studio

E. G. Kraft – artist-researcher, founder

Anna Kraft – researcher, director

Contact:

mail[at]kraft.studio

Studio Addresses

Ikejiri, Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan

Neubau, Vienna, Austria

Contact

mail[at]kraft.studio

Studio

E. G. Kraft – artist-researcher, founder

Anna Kraft – researcher, director